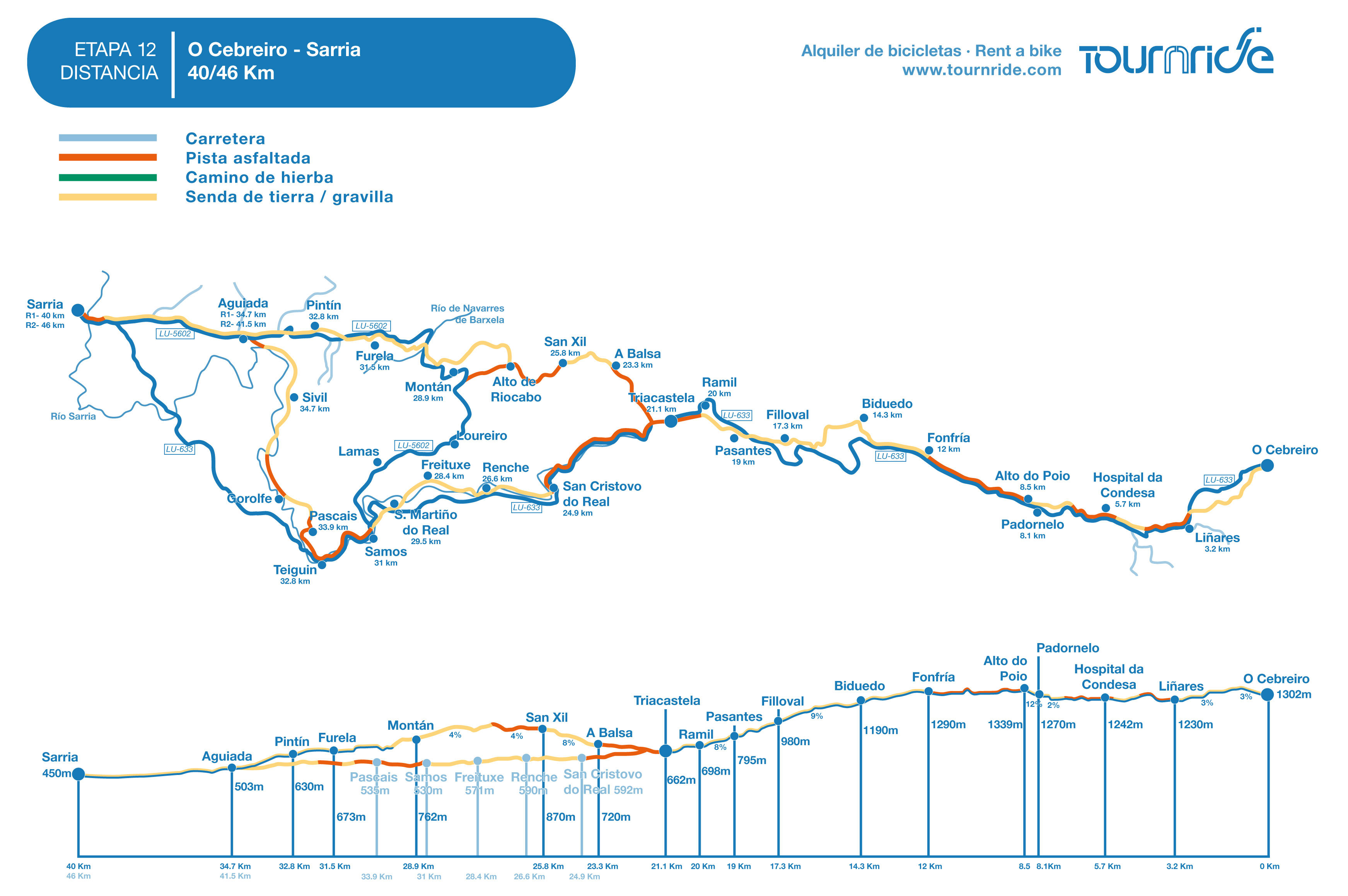

STAGE 12: FROM O CEBREIRO TO SARRIA

Erea FabeiroFRENCH WAY ON BIKE

- Distance to Santiago: 150 km

- Distance for stage: San Xil Via 40 km / Samos Via 46 km

- Estimated time: 5 – 7 hours

- Minimum height: 450

- Maximum height: 1339 m

- Route difficulty: Median

- Places of public interest: Triacastela, Samos, Sarria

- Itinerary map: To see the whole journey on Google Maps click here

In this stage, we notice a big change regarding the community. We leave Castilla and León behind and we get into Galicia: “Legbreaking” ways, a huge number of small towns and immersion in the green rural area. You won’t find large cities until you get to Santiago, but today we will end up in Sarria, where we will find all the services we need.

Today’s route is characterized by starting with a pronounced descent from O Cebreiro, alternate with two jumps with small-slopes shape. From el Alto do Poio the profile will be in a continuous descent until Triacastela.

In Triacastela we must choose an itinerary, because we have two variants. The traditional way, which is shorter and more direct (although with a complicated profile), is the one from San Xil, to the North. The South variant is 6, 5 km longer, but the detour is worth it because we can visit the monastery of Samos, one of the most monumental monastic complexes of Galicia.

In the next lines we tell you in a very detailed way all about this stage… Tournride wishes you buen camino!

GENERAL PROFILE AND JOURNEY OF THE STAGE

This stage has a first common route, from O Cebreiro to Triacastela. In Triacastela the way forks and connects again in 5, 5 km before arriving to Sarria, in Aguiada.

To Triacastela, we can choose to use the pedestrian paths or follow the course of the LU-633. The road can be chosen once we are in O Cebreiro (in the septentrional part of town) and leads us directly, passing by all the towns of the stage. The profile is more constant by the pedestrian paths, with fewer jumps. Even so, since we go out of O Cebreiro we have to ascend first to el Alto San Roque and then to the one from Poio (1339 m, maximum height of the French Way in Galicia). From el Alto de Poio we descend until Triacastela, first softly and then with slopes up to 17%.

If we go from O Cebreiro to Triacastela on bike by pedestrian paths, we surely will have to get off the bike and push it through at some point of the road, especially in the two first ascents to the heights. The surface is really stony in a lot of the points of the paths, whether it’s ascending or descending.

The pedestrian itinerary goes out of the paved way next to the municipal shelter. This leads us to a narrow path that later flows into a wide forest track and in a few meters, into the LU-633, in order to enter to Liñares (3, 2 km). By a parallel path to the highway we continue moving forward until arriving to el Alto de San Roque and later until Hospital de la Condesa (5,7 km).A few meters after, passing by Hospital de la Condesa, the route splits up one more time from the LU-633 in order to pass by Padornelo and ascend to el Alto de Poio, but in Tournride we recommend you to continue this part by road. The final ascending slope has a medium inclination of 13% and is made up by big loose stones.

From el Alto de Poio (8, 5 km) the pedestrian path is made of stone, it’s not really that wide and goes through the LU-633 in parallel. After passing by Fonfría (12 km) the road and the path split up right before getting to O Biduedo. The Jacobean ways that connect O Biduedo (14, 3 km), Filloval (17, 3 km), Ramil and Triacastela (21, 1 km) have a land surface, and sometimes it has stones, but they’re completely bicycles.

In Triacastela, the way forks until getting to Aguiada: we can go by San Xil (14 km of route) or by Samos (20, 5 km of route). The way by San Xil has a more complicated profile than the one by Samos, and at the first half we don’t have any option to circulate by road, we have to do it by paths. The route forks at the end of the main street of Triacastela, indicated by two signs.

- The route by San Xil changes course to the North, by a concrete track that goes out of the LU-633 indicating “San Xil” and that it takes us to A Balsa with a medium slope of 8%. The stretch from there to San Xil (25, 8 km) it’s travelled by paths with a complicated surface with several jumps, although we can avoid this by following the previous concrete track. From San Xil the slope gets soft until el Alto de Riocabo, the highest height of this alternative way (890 m).

From this point, the way gets into the forest and it has a permanent descent, first with a slope of 4% until Montán (28,9 km) and then a little bit more constant but with marked jumps passing by Fontearcuda (29,6 km), Furela (31,5 km) and Pintín (32,8 km). The first part between el Alto de Riocabo and Montán is done by a road where we have to be extremely careful, because there’s a big stone stretch that creates natural stairs. We can avoid this by following the road until the crossroad with the LU-5602 that goes directly to Sarria passing by all the towns from this stage.

- We take the route by Samos by turning to the left in Triacastela and it has a very simple profile (the maximum height is 592 m). The LU-633 continues the majority of its itinerary passing by all its towns until Teiguín, following town to Samos. In Teiguín, the road goes to the West, directly to Sarria, but the pedestrian way leaves the road behind to connect with the North of the San Xil road.

In the first part of the route, from Triacastela to San Cristovo (24, 9 km), pilgrims on foot join us by the shoulder of the LU-633. Before entering to San Cristovo the path splits up from the road and connects again in Renche (26, 6 km). Once again, it forks at the exit of town and passes by Freituxe (28, 4 km) and San Martiño do Real (29, 5 km). If we go by road we will not pass by Freituxe. San Martiño is not that far away from Samos, which we leave behind by the LU-633. After passing by Teiguín a Jacobean sign leads us to a concrete track in a slope that goes out to the right of the road. If we take it, we will pass by Pascais (33, 9 km), Sivil (39, 8 km) and Calvor until flowing into Aguiada, where we can follow the LU-5602 until arriving to Sarria. If we want to shorten the way it’s better to follow the LU-633 from Teiguín until Sarria, avoiding the detour.

As you see, this stage gives a lot of opportunities on the itinerary, because we can choose all the time between going by the pedestrian way or by the road and besides we have two more routes that we can choose almost at the end of the stage, with connections between them or directly to Sarria. Choosing one way is a personal decision and any of them will be a good memory for us, because every single one of them goes through an amazing natural environment. The road is also one of the most beautiful ones from the inside of the community, and one of its stretches is the highest one of all the road networks in Galicia.

Due to how many times you ask for some advices on which route to take, we leave you the route that here in Tournride we advise you to follow in order to combine security with visits to Jacobean towns with the most patrimony, always giving priority to the pedestrian ways. If the weather condition is bad or there’s an excessive pilgrims’ affluence, we recommend you to go by road with the appropriate security signs:

- O Cebreiro – Alto do Poio: LU-633

- Alto do Poio – Triacastela: pedestrian route increasing precaution

- Triacastela – Sarria:

- Route by San Xil. Follow the pedestrian way to A Balsa. Road from there to Montán. From Montán to Sarria, go by pedestrian paths.

- Route by Samos. Use the pedestrian paths. From Teiguín it gets easier following the LU-633, but the Jacobean way that connects with Aguiada is totally bicycle.

PRACTICAL ADVICES

- A lot of pilgrims on foot start their way in O Cebreiro, although not many cyclists do it because the whole journey does not represent the minimum distance to get the Compostela (you must cover 200 km minimum). Even so, each one of them must decide what to do according to their time and appetence so, as always, we leave you the information about how to get to O Cebreiro.

In this case, there are not buses (not even train or airplanes!) that go directly to O Cebreiro. The best thing to do is going to Piedrafita do Cebreiro, which Alsa can offer you many connections from Lugo and Santiago. It is also connected to large cities such as Madrid or Barcelona, although with less frequency. Once we are in Piedrafita we don’t have any other option but taking a taxi or walk to the town, it’s about 3,5 km and the taxi price can be about 10€.

Besides, you already know that in Tournride we leave your bikes during the previous day at the beginning of your trip in the lodging that you chose back in O Cebreiro. Also, we can also take your extra bagage to wait for you at the end your road, so you won’t have to carry with extra weight!

- Be careful with getting lost from Triacastela to Samos. There are not that many vertical Jacobean signs, you will mostly find yellow arrows. There are times that those arrows can be a little modified with the purpose of making pilgrims pass by some private stores. Besides, in this area they have trail running races and there are blue arrows marked on the trees to guide contestants, please remember that our arrows are only the yellows ones, we follow the roots of Valiña! If you look a little into our stage map before going out, or print our stage map on PDF, you won’t have any trouble.

- If you go by pedestrian ways, you must be extra careful with the road crossroads, there are too many!

- As we advised you in the previous stage, you have to pay attention to the weather, it changes a lot and can make you choose another specific itinerary, especially when it’s really windy, rainy or with snow. If it’s raining or snowing or with excessive affluence of pilgrims in Tournride we advise to make the entire route by the LU-633.

- In Galicia you will find some small towns every few meters, so it’s not really necessary to carry with extra food or drinks. Even so, some of the towns from this stage (especially the ones from the San Xil route) do not welcome pilgrims on their stores or shops, because they’re completely rural. So that’s why in many of them you won’t find any kind of service.

- If you choose the variant to Samos because you want to visit the monastery, we recommend you to look firstly the day before, the visit schedules, because they have too many.

DETAILED ITINERARY AND HISTORIC-ARTISTIC PATRIMONY

Just like in the previous stage, this part of the French Way joins together a huge landscape and natural interest with the stop at some monumental enclaves with huge patrimonial importance, such as the monastery of Samos. Meanwhile, we will pass by dozens of small rural enclaves, a habitable configuration very typical from Galicia; where in the rural part they live “close but separated”. No wonder in Galicia there are 39% of the town centers of Spain, although only 5,8% of the country’s population live there!

The first part of the stage, until Fonfría, we will travel it by the highest part of the road of Galicia that goes through los Ancares . This natural and political border that we have crossed in the previous stage has been declared Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO. It preserves its nature in its entire splendor and due to the complicated land configuration, it has always been in an isolation situation, which has favored the preservation of the traditions and popular architecture. We could see this already back in O Cebreiro, with its pallozas and granite and slate houses, but today it’ll be more noticeable because we see more towns in the distance and go through some of them.

After, we go to Sarria by the North limit of la Sierra do Courel, one of the most important natural protected areas of Galicia. It covers more than 21000 hectares, full with valleys between mountains with a Mediterranean and Atlantic forest. Dozens of species live there, a lot of them also protected. There are wolves (but don’t worry, they run away from humans) and real eagles and owls, although they’re hard to find each time. Before, there were grizzly bears, even though today their habitat in Galicia is reduced to only Los Ancares.

Welcome to the apostle land!

FROM O CEBREIRO TO TRIACASTELA, THE PERFECT MOUNTAIN STRETCH

We leave O Cebreiro behind and, by path or road; we arrive in less than 3 km until Liñares, first town of the stage. With less than 70 people which most of them work on agriculture and on livestock production, this town welcomes pilgrims with its church dedicated to San Esteban (Santo Estevo in Galician) which people believe was founded in the VIII century. In the past, this parish depended of the important monastery of Santa María do Cebreiro, to whom they provided linen, that’s where its current name comes from.

The pedestrian way crosses at the exit of Liñares and follows a stone path until getting to el Alto de San Roque first, and el Alto de Poio later. It’s a legbreaking road, with continuous ascents and descents. Also we can go by the LU-633.

El Alto de San Roque (1275 m of height) is marked with an outstanding bronze statue. The Galician sculptor Jose María Acuña made it in 1993 and tried to reflect the hardness of the way that pilgrims must travel by those ports. Dressed up with medieval Jacobean clothing, he’s holding his hat with one hand so the wind won’t take it away, while he supports himself on his walking stick to continue ascending. The surroundings views from this point are very impressive.

From this point, the descent is a little steep by pedestrian paths, although by road we can descend in a softer way. We pass by Hospital de la Condesa (km 5, 7), called like this because in the past it had a hospital dedicated to serve pilgrims, maybe sponsored by some aristocrat.

From Hospital de la Condesa, the pedestrian way goes through a gravel path parallel to the right shoulder of the road and splits up from it 800 meters after, in a detour to the right. This detour takes us to Padornelo and from there to Alto de Poio, where it passes by the LU-633 again. In this stretch of the ascent to Alto de Poio we recommend doing it by road because of how stony the surface is and how heavy the final slope can be, only 300 m long but very inclined.

El Alto de Poio is, with its 1339 meters of height, the highest point that we will step in during the entire journey through Galicia. This offers a very impressive view of the entire surrounding mountains.

From el Alto de Poio to Fonfría there are 4 km that pedestrians walk by the left shoulder of the road. We cover them quickly because the profile is practically flat.

Fonfría (km 12) is a small town which name derives from “fonte fría” (“Cold fountain”, in Galician), in reference to the spring water. In this case, we still see a fountain at the entrance of town and runs water from the Reñadoiro Mountains.

After covering 1 km from Fonfría we enter to the municipality of Triacastela and the first town that we visit in this part is O Biduedo (km 14, 3), where a simple chapel dedicated to San Pedro is located at. In the Lugo area, a lot of birches come up (“bidueiros” in Galician) in the river’s shore, which in the past this town had a lot of them, that’s where the town’s name comes from.

From O Biduedo the road’s line and the pedestrian way go apart, so the second one will go into the mountain. The majority of stretch is bicycle, although there will be moments where the surface is composed of stone chips, so we recommend you to have caution.

This mountain was the setting, in the Middle Age, of a very symbolic tradition, which it’s told in the Códice Calixtino. People say that in the eleventh stage, which went from Villafranca del Bierzo to Triacastela (Aymeric was riding a horse, covering long distances), pilgrims must choose a stone from these mountains of Triacastela and carry it with them until getting to Castañeda, where they passed by their final stage, which went from Palas to Compostela. They should leave it in Castañeda, in the lime ovens of the town, where they used to prepare the mortar in order to build the cathedral. Just like this, every pilgrim could contribute in a small way, to raise La Casa de Santiago.

We pass by the small town of O Filloval (km 17,3) or O Fillobal, or however we want to call it, because this town’s name can be written with “b” or “v” or with the article or not… No one really is clear about the correct way to write it, not even in Galician not even in Spanish! After dealing with this confusing orthographic point, the way crosses with the LU-633 in order to cross Pasantes, to the other side of the road. Right before entering into Triacastela we pass by Ramil, a small rural enclave that keeps a natural treasure: a big hundred-year-old chestnut. We don’t know the exact age of this tree, but we believe it may have around 800 years of age!

In Ramil we are practically located at the entrance of the urban center of Triacastela, where we get to by a land path between trees and grass areas. Once we are in Triacastela, we will realize that in this Jacobean village, the impact of the Camino de Santiago and its pilgrims’ affluence is really strong, especially if we visit from June to September.

This affluence is not really new, because pilgrimage was already rising up in the XII and XIII centuries, Triacastela had already more pilgrims than visitors. In fact, people say that in the Códice Calixtino a lot of caterings from Compostela got closer to Triacastela in order to convince pilgrims to stay in their inns when they arrive to Santiago. They promised them to be the best and saved a bed in exchange of payment, but a lot of times when pilgrims arrive they saw that the lodging was completely bad and didn’t fill their expectations and that they charged extra money for this.

Fraud attempts were not allowed, there was even a prison for pilgrims. They locked up people who pretended to be walkers to take advantage of people’s good will and get alms, food or a free bed. This old building today is almost in completely ruins and we can see it before entering to Plaza Mayor.

Triacastela owes its name supposedly to the existence of three forts or castles in this area (Historians do not agree on this one). There are some people who say the place name derives from the fact that it was a pass to Castilla.

What’s clear is that it has a big Jacobean tradition, which is reflected in its urbanism, because its main street coincides with the Way trace and its name leaves no doubts, because it’s called rúa do Peregrino and rúa Santiago. Besides, its parish church is dedicated to the apostle and people believe that probably the old pilgrims hospital would had been connected with it. The temple’s Romantic apse is still preserved, although the rest is baroque (C. XVIII) and in its major altarpiece there’s a huge image of Santiago dressed up as a pilgrim. In the tower there’s a shield engraved with three castle’s towers, which created the theory that the town’s name derives from this fact.

Triacastela is a good place to rest and have a drink on the several stores from the hotels that we can find. Later, we should go straight through the Mayor street and choose which route to take in order to get to Sarria.

FROM TRIACASTELA TO SARRIA BY SAN XIL

The route of Triacastela to Samos was born centuries ago by the influence of the imposing monastery that is located there, but the one of San Xil was born by the use of common sense. On bike the distances logic is not the one that weights the most, but we can really tell when we walk 5 km! Especially when we move in hard orographic just like the Galician one!

By San Xil we take less to get there and, just like the Samos road, we go through a spectacular landscape. The profile of this route is more complicated than the one from Samos, because there’s a higher physical effort on the initial slopes until el Alto de Riocabo and more technical capacity on the descent (if we travel by the pedestrian paths).

To choose this route we have to abandon Triacastela turning to the right at the end of the main street. After crossing the rod we take a concrete track with yellow arrows and signs indicating “San Xil”. This part of the way is simple and takes us to A Balsa in about 2 km, the first town on this route.

A Balsa is a small rural town where there’s a chapel dedicated to Nuestra Señora de las Nieves. Our visit will become a prelude to what come next to Sarria: colorful towns with a really small size that keeps its rural and traditional essence at its maximum, not being used to take advantage of pilgrims visitors.

From A Balsa to San Xil the pedestrian way is complicated: with jumps and stone and land surfaces that get muddy if it has been raining (very usual in this area). If you want to avoid this part you can go out of A Balsa and continue by the road. By the pedestrian way the nature vision is wilder, but on road the views are also wonderful and we can enjoy them a little bit more.

San Xil (km 25, 8) is a small town without services, but its place name indicates that probably it had a marked Jacobean past. The saint, to whom the town is dedicated, is very important in France, especially in the places where the Santiago route passes by, so probably that’s why the connection between the place and pilgrimage comes from the past.

The ascent from San Xil to el Alto de Riocabo is covered by road. It’s not really that hard, but maybe the effort we made in the previous stage has left some kind of damage and it will take us longer and harder to get there than the usual. El Alto de Riocabo will mark a change on the route’s dynamic because the descent starts there until getting to Sarria. The pedestrian way gets into the forest by “corredoiras”, land and stone ways between big oaks or “carballos”, as natives would say.

Some parts of this descent are quite complicated, including the stretch with big stones that are placed together as if they were stairs. With the rain, it gets a little slippery and due to the fact that it descends we must put in practice our best technique abilities. If we are not capable of doing it, the best thing to do is to avoid the detour in el Alto de Riocabo and continue by the concrete track. We will flow into the LU-5602 and from there we can follow the road until Sarria or changing course to the pedestrian way in any of the several crossroads between both.

The following town where we can arrive, whether it’s by path or by road, is Montán. The way doesn’t really enter to this small rural town and from here until Sarria, the paths are much more bicycle than the one that have guided us from Triacastela.

If we want, we can change course to the town in order to see the church of Santa María de Montán. The temple is Romantic, simply made of masonry and slate, with an entrance portico where a small window opens over it. In the inside, the ship’s height stands out, which by the way it looks lower from the outside. The major altarpiece is Neoclassic (C. XIX)

Leaving Montán behind, we continue pedaling on a light descent to Fontearcuda (km 29, 6) and, from there; a land path takes us to cross the LU-5602 and a river. After, we pedal 700 meters more between fields and we flow into the road again.

The road passes by the middle of Furela (31,5km) only 500 meters later, and after passing it by, we enter already to Sarria municipality. In this small town without services, there’s a simple chapel dedicated to San Roque, white painted on the outside and with a bell gable on the main cover. After bordering the chapel, the path crosses again the road and The Way keeps going parallel to the road, and little by little it gets apart until entering to Pintín.

From Pintín (km 23, 8) to Aguiada we go firstly by concrete and later by a path located within the forest. The surface can turn a little bit complicated, because it’s stony and if it rains it can get muddy. If this is not the case, we can always go through the LU-5602. In Aguiada (km 34, 7) we reunite again with pilgrims that have been doing the Way by the route of Samos and we will travel the next 5 km with them until getting to Sarria.

Aguiada is a small town with less than 50 people, that has the pilgrims services and a small rural chapel dedicated to Nuestra Señora de la Asunción.

From Aguiada, el Camino goes permanently connected to the LU-5602, so for us it will be much comfortable going by the shoulder.

Some pilgrims in the Middle Age (considering how difficult it was back then to cover each kilometer!) even decided to increase their distance of their Way just with the purpose of passing by the wonderful monastic enclave of Samos, this place must’ve had something really special!

A lot of pilgrims on foot decide to go by the route of San Xil to avoid in the maximum the concrete stretches, because this route has a lot of them. For us, this can be in our favor, because we can go by road without much traffic after covering the hard stage on the previous day, whose profile is simpler than the one of San Xil. Besides, the journey by concrete blocks our view of the amazing natural landscape that surrounds us during the whole route: hundred year-old trees typical of the riverbank Atlantic forest: such as oaks, chestnuts, birches.

In order to go by this route we must turn to the left at the end of the main street of Triacastela, passing by the City Council and la Plaza de la Diputación. Later, the arrows will indicate us to go back to the LU-633. The first 4 km until San Cristovo do Real are covered by road, in a light negative slope.

In this stretch by concrete, the fact that some road’s parts fit in between high vertical stone walls may attract our attention. We are going over el Desfiladero de Penapartida, this is a place that, according to the legend, was built during the pilgrimage of the Virgin to Compostela. When she got to this area she found a huge rock blocking her way, so she called two angels that descended from heaven bringing with them a big lightning that split the rock in two, creating this natural environment that centuries later was taken to build the road.

From the road, a detour to the right takes us to a gravel path in a strong slope where we enter to the village of San Cristovo. This small village with less than 35 people seems to have been stopped in time, because it preserves a lot of its popular architecture (although some examples are in a better state preservation than the others). Its parish church (C. XVII) becomes important thanks to its major altarpiece, a churrigueresque jewel hidden in the Galician rural. The Oribio River passes by the middle of the town and its shores are full with big trees. In order to go out of town we must cross the flow by a bridge and, after, we immerse ourselves in the forest by corredoiras and big tracks between trees.

During the next 5, 5 km from San Cristovo to San Martiño do Real, the way goes all over the whole nature. Even though there are some parts with a lot of jumps and some parts have the surface a little bit unstable. The only exception when we don’t make this time perfectly on bike is when it rains a lot.

Going out the village of San Cristovo we pass by a public shelter Casa de Lusío, which is located at an old country house from the XVI century, whose last owner gave this Benedictine community of Samos up. This, at the same time, gave it up to the Xunta de Galicia that started to restore it in 2007 in order to get back its function that it had in the past, hostelry. In the actuality, the old rooms of the residency are full of bunk beds and rest areas for pilgrims, being restored in a modern way but sticking to its original configuration, just like its constructive elements, for example its external arches, its shield (marked with eight scallops) or its big conical chimney located at the same spot where the kitchen was before. The old country house is bordered by a 15 hectares farm, where there are stables, a mil, a smithy or a chapel.

The shelter also counts with some areas dedicated to exhibitions and museums. The main idea was to install a permanent exhibition in there about Vicente Vázquez Queipo de Llano, a mathematician, physician and politic that was born in this country house in 1804. The most popular thing about his legacy was his development on the logarithm tables that are still used in the actuality; he even received a prize from The International Exposition of Paris in 1867.

We cover less than 2 km in order to get to Renche by ways covered with leaves from the top of the trees, where the light finds a way to draw fanciful shapes that let loose our imagination and transports us to a fantastic world (not for nothing”El bosque animado” was inspired on this Galician forest).

Renche (km 26, 6) is located in the actuality at the border of the LU-633 and it’s a small rural town that the Pope granted to the monastery of Samos in the XVI century, with the condition that monks should go there every day with food and wine for pilgrims. The church is dedicated to the apostle, although its biggest attraction is, without doubt, the wonderful natural environment, where we immerse ourselves when we go out of the town in order to cover another 2 km until Freituxe.

In this stretch from Renche to Freituxe the surface and the profile change a lot, because there are some land, stone or gravel slides. We get to Freituxe (km 28, 4) by ascending. We won’t find that many services in this town and, after passing it by, the most complicated part of this route is waiting for us, especially because of the surface, where there are big loose stones. It’s important to be extra careful and, if we want to avoid it, we don’t have any other option than going directly by road from Renche to San Martiño without passing by Freituxe. Although in this case, it would be such a shame to miss this beautiful natural environment.

In San Martiño do Real (km 29, 5) we are one more time at the border of the LU-633. We are getting closer to Samos each time, but maybe you deserve a stop at the church dedicated to San Martín in this town, if you are interested in the rural Romanticism. Just like the one from Montán in the San Xil route, the materials are simple, made of masonry and slate and it doesn’t have a lot of decoration. It also has a portico at the entrance, which it’s a reflection of the weather’s hardness on the area, where it’s necessary to find a shelter where to protect ourselves in case of rain or snow.

At the exit of the town, the pedestrian way crosses the road by a lower tunnel and, after a sign and yellow arrows indicate the crossroad (without pedestrian pass) of the LU-5601. By a path between trees, with an irregular surface and legbreaking profile, we arrive to Samos.

Before entering to Samos, the Way takes us to a higher height, where we can appreciate spectacular views of the monastery, before arriving to the actual destination.. From there we go down in a pronounced way until getting the urban center. If we go by road we enter to town by the North and the views are not really that good.

Once we are in Samos (km 31), we will find all the services and we can make a stop to enjoy the wonderful monastery, that has almost 1500 years of being a monastic room, only interrupted during a short period of time from the XIX century.The monastery of San Julián de Samos had a lot of political, social and spiritual influence on its nearest surroundings and in larger scale. Some important intellectual people and kings used to stay in there, some of them were connected to pilgrimage.

The origins of this monastery go back to the VI century, when San Martín de Dumio promoted the settlement of a monks group in this unexplored place between mountains. San Martín Dumiense was a bishop and theologian who was born in Hungary and, after visiting los Santos Lugares in the East, he even became bishop of Braga. The influence was that big that it even got to change the official Swabian religion from Arianism to Catholicism and encouraged the humble people to leave aside the cults inherited from the Roman Times and get closer to Christians. The monasteries founded under their orders, were controlled under the rules with Hispanic-Visigoth origins, like the one developed by San Fructuoso a century ago in El Bierzo, or the one San Isidoro wrote in Sevilla. Over the centuries the church decided to unify the rules, eliminating these types of rules to change all of them for the Benedictine of Cluny, a process that ended in the XII century.

This change took place in Samos in the X century, when they eliminated the San Fructuoso Rule for the “ora et labora” Benedictine. Given the connection between The Cluniac Reforms with el Camino de Santiago and with the Crown, the monastery gained each time more importance. In the C. XVI its biggest moment of magnificence arrived, in that century, eight soon-to-be bishops and big religious intellectuals came out of its walls. One of them was Father Benito Feijoó, who promoted the illustration in Spain and he was one of the first people who wrote essays in the peninsula, including some of the controversial ones such as “En defensa de las mujeres”, that claimed for equality in a century when the situation was really far away from being equal.

In the XIX century, the peace and intellectuality environment of the monastery changed drastically when it became a hospital where injured people were taken care of during the Independence War. Later, with the Confiscation, they had to leave the building but the monks could occupy the place again 24 years later.

Since then, this magnificent complex has been occupied by monks who continue “praying and working”, including offering service to pilgrims for hostelry located at the monastery. Due to this being a historic-artistic monument, there is a schedule for tourist visitsthat we recommend checking up the day before in order to organize the arrival of Samos when it’s open.

Despite its old origins, the majority of what we see today come from the Renaissance and Neoclassicism times (C. XV-XVII), from “the gold times” of the monastery. It’s curious the fact that, although everything was made in a monumental way and with big dimensions, they still wanted to pretend sobriety. That’s why there is not a lot of decoration. From the complex, mainly four parts stand out: its church, the cloisters, the library and the so called Chapel of Cypress.

The Church’s facade is missing two towers that they never got to be built, that’s why it looks a little “squat”. It has an external stair that we should keep in our memory, because it will remind us of the cathedral from Compostela.

In the inside of the monastery there are four cloisters, which one of them is the biggest of Spain. It’s dedicated to Father Feijoó and, in its center, a huge sculpture made by the artist Francisco Asorey, who was one of the sculpture’s renovators from the XX century; represented the habits while holding big books.

The other cloister is the one from “las Nereidas” (The Nereids), known like this because a baroque fountain in its center represent four mythological nymphs holding a coup. You’re telling an anecdote by saying that some stonemason from the XVI century decided to fool visitors, carving in a hieroglyph the phrase “What are you looking at, fool?” in one of the arches’ key.

The Chapel of Cypress is separated a little from the complex. It’s much older (C. IX) and its name comes from the hundred-year-old tree raised up monumentally right next to one of its walls. The cypress is marked with a characteristic black mark, as a result of a lightning that fell directly into it during a storm. The chapel certainly, in its beginnings, could have been a monastic cell.

After leaving Samos the arrows of the Way guide us to continue by the road’s shoulder and, after, by a path between the Sarria River and the LU-633. The path gets wide open in some points to create recreation areas next to the river; this is a very nice place to rest for a while if we haven’t done it before in Samos.

Short after 1 km of Samos we will see to our right Teiguín (km 32, 8), a small town located at the right shoulder of the road. After passing it by, a vertical Jacobean sign indicates a detour directing to a slope to the left that abandons the LU-633 in order to get into the forest.

Following the detour we connect again with pilgrims of the San Xil route in Aguiada, alternating land stretches with concrete ones while we follow the course of Sarria. If you prefer going a little bit more direct you can follow the LU-633. In 9 km you will get to the end of the stage, alternating ascents and descents with no too many jumps.

If we take the detour we will begin a quite strong ascent by concrete until Pascais (km 33,9) and, from there we will descend a little until we see a small stream where is located the church of Santalla or Santa Eulalia de Pascais, another example of a Romantic hidden construction, in the Galician rural. From all of the things done in the XII century, they still preserve the apse, the North wall and one of the doors; the rest is baroque. What really attracts attention is the quality of its major altarpiece, so if you have the chance we will encourage you to see it.

We border the church by a “corredoira” between trees we get to Gorolfe, where we connect again to a concrete track that takes us to cross the Sarria River. After crossing it we continue alternating path and concrete in order to pass by Sivil (km 39, 8), from where we will be very closet o Calvor and join the rest of pilgrims in Aguiada (km 41, 5).

From Aguiada we have, just like in the other route, 5, 5 km left to get to Sarria. We can cover them by the pedestrian way, which the majority of it is connected to the road or we can pedal directly by the LU-5602.